what did the british navy try to stop the americans from doing

The American Revolutionary War saw a serial battles involving naval forces of the British Regal Navy and the Continental Navy from 1775, and of the French Navy from 1778 onwards. Although the British enjoyed more numerical victories, these battles culminated in the surrender of the British Army force of Lieutenant-General Earl Charles Cornwallis, an event that led directly to the beginning of serious peace negotiations and the eventual end of the war. From the start of the hostilities, the British North American station under Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves blockaded the major colonial ports and carried raids against patriot communities. Colonial forces could do little to stop these developments due to British naval supremacy. In 1777, colonial privateers fabricated raids into British waters capturing merchant ships, which they took into French and Spanish ports, although both were officially neutral. Seeking to challenge Britain, France signed ii treaties with America in February 1778, but stopped short of declaring state of war on Britain. The risk of a French invasion forced the British to concentrate its forces in the English Channel, leaving its forces in Due north America vulnerable to attacks.

France officially entered the state of war on 17 June 1778, and the French ships sent to the Western Hemisphere spent nearly of the year in the Due west Indies, and simply sailed to the Thirteen Colonies from July until November. In the beginning Franco-American entrada, a French fleet commanded past Vice-Admiral Comte Charles Henri Hector d'Estaing attempted landings in New York and Newport, but due to a combination of poor coordination and bad weather, d'Estaing and Vice-Admiral Lord Richard Howe naval forces did not engage during 1778.[i] Afterwards the French fleet departed, the British turned their attention to the south. In 1779, the French fleet returned to assist American forces attempting to recapture Savannah from British forces, however failing leading the British victors to remain in control till tardily 1782.[2]

In 1780, some other fleet and half dozen,000 troops commanded by Lieutenant-Full general Comte Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau, landed at Newport, and shortly later on was blockaded by the British. In early on 1781, General George Washington and the comte de Rochambeau planned an attack against the British in the Chesapeake Bay surface area coordinated with the arrival of a large armada commanded by Vice-Admiral Comte François Joseph Paul de Grasse from the West Indies. British Vice-Admiral Sir George Brydges Rodney, who had been tracking de Grasse around the West Indies, was alerted to the latter's difference, but was uncertain of the French admiral's destination. Assertive that de Grasse would return a portion of his armada to Europe, Rodney detached Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood and 15 ships of the line with orders to find de Grasse'southward destination in North America. Rodney, who was ill, sailed for Europe with the residue of his fleet in society to recover, refit his fleet, and to avert the Atlantic hurricane season.[3]

British naval forces in N America and the Due west Indies were weaker than the combined fleets of France and Spain, and, after much indecision past British naval commanders, the French fleet gained command over Chesapeake Bay, landing forces near Yorktown. The Royal Navy attempted to dispute this command in the key Battle of the Chesapeake on five September merely Rear-Admiral Thomas Graves was defeated. Protected from the ocean by French ships, Franco-American forces surrounded, besieged and forced the surrender of British forces commanded by General Cornwallis, last major operations in Northward America. When the news reached London, the authorities of Lord Frederick North fell, and the following Rockingham ministry entered into peace negotiations. These culminated in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, in which King George III recognised the independence of the United States of America.[iv]

Early on actions, 1775–1778 [edit]

First skirmishes [edit]

The Battle of Lexington and Hold on 19 April 1775 drew thousands of militia forces from throughout New England to the towns surrounding Boston. These men remained in the area and their numbers grew, placing the British forces in Boston under siege when they blocked all land access to the peninsula. The British were still able to sail in supplies from Nova Scotia, Providence, and other places because the harbour remained nether British naval control. [5] Colonial forces could do nothing to stop these shipments due to the naval supremacy of the British fleet and the consummate absence of whatever sort of insubordinate armed vessels in the jump of 1775.[A] Even so, while the British were able to resupply the city by body of water, the inhabitants and the British forces were on short rations, and prices rose quickly [6] Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves commanded the Regal Navy around occupied Boston under overall leadership of Governor General Thomas Gage.[7] Graves had hired storage on Noddle'due south Island for a multifariousness of important naval supplies, hay and livestock, which he felt were important to preserve, owing to the "almost impossibility of replacing them at this Juncture".[8]

During the siege, with the supplies in the metropolis running shorter by the day, British troops were sent to the Boston Harbour to raid farms for supplies. Graves, apparently acting on intelligence that the Colonials might make attempts on the islands, posted baby-sit boats near Noddle's Island. These were longboats that included detachments of Marines.[eight] Sources disagree equally to whether or non whatsoever regulars or marines were stationed on Noddle'southward Isle to protect the naval supplies.[B] In response, the Colonials began clearing Noddle's Isle and Hog Isle of anything useful to the British.[C] Graves on his flagship HMSPreston, taking notice of this, signalled for the guard marines to land on Noddle's island and ordered the armed schooner Diana, under the command of his nephew Lieutenant Thomas Graves, to canvass up Chelsea Creek to cut off the colonists' route.[8] This contested action resulted in the loss of two British soldiers and the capture and burning of Diana.[nine] This setback prompted Graves to motility HMSSomerset, which had been stationed in the shallow waters between Boston and Charlestown, into deeper waters to the eastward of Boston, where it would have improved manoeuvrability if fired upon from state.[10] He as well tardily sent a detachment of regulars to secure Noddle's Isle; the colonists had long earlier removed or destroyed anything of value on the island.[eleven]

The demand for building materials and other supplies led Admiral Graves to authorise a loyalist merchant to transport his ii ships Unity and Polly from Boston to Machias in the District of Maine, escorted by the armed schooner Margaretta under the control of James Moore, a midshipman from Graves' flagship Preston.[12] Moore also carried orders to recover what he could from the wreck of HMSHalifax, which had apparently been run ashore in Machias Bay past a patriot pilot in Feb 1775.[thirteen] Later on a heated negotiation, the Machias townspeople seized the merchant vessels and the schooner afterward a short battle in which Moore was killed. Jeremiah O'Brien immediately outfitted one of the 3 captured vessels[D] with bastion,[Due east] armed her with the guns and swivels taken from Margaretta and changed her name to Machias Freedom.[14] In July 1775, Jeremiah O'Brien and Benjamin Foster captured ii more British armed schooners, Diligent and Tatamagouche, whose officers had been captured when they came aground well-nigh Bucks Harbour.[15] In Baronial 1775, the Provincial Congress formally recognised their efforts, commissioning both Machias Liberty and Diligent into the Massachusetts Navy, with Jeremiah O'Brien as their commander.[16] The customs would be a base for privateering until the war's finish.[17]

British ships Phoenix and Rose engaged by colonial fire ships and galleys

Their resistance, and that of other littoral communities, led Graves to authorise a reprisal expedition in October whose sole meaning human action was the Burning of Falmouth.[xviii] On 30 August, Regal Naval Helm James Wallace, commanding Rose fired into the town of Stonington, later on the townspeople there prevented Rose 's tender from capturing a vessel it had chased into the harbour.[19] Wallace as well fired on the town of Bristol, in October, after its townspeople refused to deliver livestock to him.[20] The outrage in the colonies over these action contributed to the passing of legislation past the 2d Continental Congress that established the Continental Navy.[16] The US Navy recognises 13 October 1775, as the appointment of its official institution —[21] the 2d Continental Congress had established the Continental Navy in late 1775.[22] On this day, Congress authorised the buy of ii armed vessels for a cruise against British merchant ships; these ships became Andrew Doria and Cabot.[21] The first ship in commission was Alfred purchased on 4 November and deputed on iii December past Helm Dudley Saltonstall.[23] John Adams drafted its offset governing regulations, adopted by Congress on 28 November 1775, which remained in event throughout the Revolution. The Rhode Island resolution, reconsidered by the Continental Congress, passed on 13 December 1775, authorising the building of thirteen frigates inside the side by side iii months, five ships of 32 guns, five with 28 guns and three with 24 guns.[24]

[edit]

Alfred, one of the offset ships in the Continental Navy preparing for her maiden voyage

The drastic shortage of gunpowder available to the Continental Army had led the Congress to organise a naval expedition, one of whose goals was the seizure of the war machine supplies at Nassau.[25] While the orders issued by the Congress to Esek Hopkins, the fleet helm selected to lead the expedition, included merely instructions for patrolling and raiding British naval targets on the Virginia and Carolina coastline, additional instructions may take been given to Hopkins in hugger-mugger meetings of the Congress' Naval Commission.[26] The instructions that Hopkins issued to his fleet's captains before it sailed from Cape Henlopen, Delaware on Feb 17, 1776, included instructions to rendezvous at Dandy Abaco Isle in the Bahamas.[27] The fleet that Hopkins launched consisted of: Alfred, Hornet, Wasp, Wing, Andrew Doria, Cabot, Providence, and Columbus. In addition to ships' crews, it carried 200 marines under the command of Samuel Nicholas.[28] In early on March, the fleet (reduced by one due to tangled rigging en route) landed marines on the isle of New Providence and captured the town of Nassau in the Commonwealth of the bahamas.[29] Afterward loading the fleet's ships, (enlarged to include two captured prize ships), with military machine stores, the fleet sailed northward on 17 March, with ane ship dispatched to Philadelphia, while the rest of the armada sailed for the Cake Island aqueduct, with Governor Browne and other officials as prisoners.[thirty] Outbreaks of a multifariousness of diseases, including fevers and smallpox, resulting in significant reductions in crew effectiveness, marked the fleet'southward cruise.[31]

The return voyage was uneventful until the fleet reached the waters off Long Isle. On 4 April, the fleet encountered and captured a prize, Hawk, which was laden with supplies. The adjacent day brought a 2d prize Bolton, which was also laden with stores that included more armaments and pulverization.[32] Hoping to catch more than like shooting fish in a barrel prizes, Hopkins continued to cruise off Cake Isle that nighttime, forming the fleet into a scouting formation of 2 columns.[33] The need to homo the prizes farther reduced the fighting effectiveness of the fleet's ships.[31] The fleet finally met resistance on April six, when it encountered the Glasgow, a heavily armed 6th-rate transport. In the ensuing action, the outnumbered Glasgow managed to escape capture, severely damaging the Cabot in the process, wounding her helm, Hopkins' son John Burroughs Hopkins, and killing or wounding eleven others.[34] Andrew Doria's Helm Nicholas Biddle described the battle as "helter-skelter".[33] They reached New London on eight Apr.[35]

Although Continental Congress President John Hancock praised Hopkins for the armada'due south performance, its failure to capture Glasgow gave opponents of the Navy in and out of Congress opportunities for criticism. Nicholas Biddle wrote of the action, "A more than imprudent, ill-conducted affair never happened".[36] Abraham Whipple, captain of Columbus, endured rumours and accusations of cowardice for a time, but eventually asked for a court-martial to clear his name. Held on half dozen May by a panel consisting of officers who had been on the cruise, he was cleared of cowardice, although he was criticised for errors of judgment.[37] John Hazard, captain of Providence, was non so fortunate. Charged past his subordinate officers with a variety of offences, including neglect of duty during the Glasgow action, he was bedevilled by court-martial and forced to surrender his committee.[38]

Commodore Hopkins came under scrutiny from Congress over matters unrelated to this action. He had violated his written orders by sailing to Nassau instead of Virginia and the Carolinas, and he had distributed the goods taken during the prowl to Connecticut and Rhode Island without consulting Congress.[39] He was censured for these transgressions, and dismissed from the Navy in January 1778 afterward farther controversies, including the fleet'due south failure to canvas again (a number of its ships suffered from crew shortages, and also became trapped at Providence by the British occupation of Newport belatedly in 1776).[40] American forces were not potent enough to dislodge the British garrison there, which was too supported by British ships using Newport equally a base.[41]

On Lake Champlain, Benedict Arnold supervised the construction of 12 vessels to protect access into Hudson River's uppermost navigable reaches from advancing British forces. A British fleet destroyed Arnold'south in the Battle of Valcour Island, simply the fleet'due south presence on the lake managed to slow down the British progression plenty until winter came before they were able capture Fort Ticonderoga.[42] By mid-1776, a number of ships, ranging up to and including the thirteen frigates approved past Congress, were under construction, but their effectiveness was limited; they were completely outmatched by the mighty Majestic Navy, and nearly all were captured or sunk by 1781.[43]

Privateers had some success with i,697 letters of marque being issued by Congress. Individual states and American agents in Europe and in the Caribbean also issued commissions. Taking duplications into account, diverse authorities issued more than 2,000 commissions. Lloyd'southward of London estimated that Yankee privateers captured two,208 British ships, amounting to almost $66 one thousand thousand, a significant sum at the fourth dimension.[44]

France enters the war, 1778–1780 [edit]

Comte d'Estaing, 1769 portrait by Jean-Baptiste Lebrun

French movements [edit]

For its start major attempt at co-performance with the Americans, France sent Vice-Admiral Comte Charles Henri Hector d'Estaing, with a fleet of 12 ships of the line and some French Army troops to North America in April 1778, with orders to blockade the British North American fleet in the Delaware River.[45] Although British leaders had early intelligence that d'Estaing was likely headed for North America, political and war machine differences within the government and navy delayed the British response, assuasive him to canvas unopposed through the Straits of Gibraltar. It was not until early June that a fleet of thirteen ships of the line under the control of Vice-Admiral John Byron left European waters in pursuit.[46] D'Estaing's Atlantic crossing took three months, but Byron (who was chosen "Foul-weather Jack" due to his repeated bad luck with the weather) was also delayed by bad weather and did not reach New York until mid-August.[45] [47]

The British evacuated Philadelphia to New York Metropolis earlier d'Estaing's arrival, and their Northward American fleet was no longer in the river when his fleet arrived at Delaware Bay in early July.[45] D'Estaing decided to sheet for New York, just its well-dedicated harbour presented a daunting challenge to the French fleet.[48] Since the French and their American pilots believed his largest ships were unable to cantankerous the sandbar into New York harbour, their leaders decided to deploy their forces confronting British-occupied Newport, Rhode Island.[49] While d'Estaing was exterior the harbour, British Lieutenant-Full general Sir Henry Clinton and Vice-Admiral Lord Richard Howe dispatched a fleet of transports carrying 2,000 troops to reinforce Newport via Long Island Sound; these reached their destination on 15 July, raising the size of Major Full general Sir Robert Pigot's garrison to over 6,700 men.[50]

French arrival at Newport [edit]

Arrival of d'Estaing's squadron at Newport on viii August 1778. Engraving by Pierre Ozanne

On 22 July, when the British judged the tide high enough for the French ships to cantankerous the sandbar, d'Estaing sailed instead from his position outside New York harbour.[49] He sailed due south initially before turning northeast toward Newport.[51] The British fleet in New York, viii ships of the line under the command of Lord Richard Howe, sailed out after him once they discovered his destination was Newport.[52] D'Estaing arrived off Point Judith on 29 July, and immediately met with Major Generals Nathanael Greene and Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, to develop a program of attack.[53] Major General John Sullivan'due south proposal was that the Americans would cross over to Aquidneck Island's (Rhode Island) eastern shore from Tiverton, while French troops using Conanicut Island as a staging basis, would cross from the west, cutting off a disengagement of British soldiers at Butts Colina on the northern office of the island.[54] The next mean solar day, d'Estaing sent frigates into the Sakonnet River (the channel to the east of Aquidneck) and into the main channel leading to Newport.[53]

Every bit allied intentions became clear, General Pigot decided to redeploy his forces in a defensive posture, withdrawing troops from Conanicut Island and from Butts Hill. He too decided to motility near all livestock into the city, ordered the levelling of orchards to provide a clear line of fire, and destroyed carriages and wagons.[55] The arriving French ships drove several of his supporting ships ashore, which were and then burned to prevent their capture. Every bit the French worked their manner upwardly the channel toward Newport, Pigot ordered the remaining ships scuttled to hamper French access to Newport's harbour. On 8 Baronial d'Estaing moved the bulk of his fleet into Newport Harbour.[52]

On 9 August d'Estaing began disembarking some of his iv,000 troops onto nearby Conanicut Island. The same mean solar day, General Sullivan learned that Pigot had abandoned Butts Colina. Opposite to the agreement with d'Estaing, Sullivan then crossed troops over to seize that loftier basis, concerned that the British might reoccupy it in strength. Although d'Estaing later approved of the action, his initial reaction, and that of some of his officers, was one of disapproval. John Laurens wrote that the action "gave much umbrage to the French officers".[56] Sullivan was en road to a meeting with d'Estaing when the latter learned that Admiral Howe's armada had arrived.[57]

Storm impairment [edit]

Lord Howe's armada was delayed departing New York past contrary winds, and he arrived off Bespeak Judith on nine Baronial.[58] Since d'Estaing's fleet outnumbered Howe's, the French admiral, fearful that Howe would be farther reinforced and somewhen gain a numerical advantage, reboarded the French troops, and sailed out to do battle with Howe on x August.[52] As the ii fleets prepared to boxing and manoeuvreered for position, the atmospheric condition deteriorated, and a major storm broke out. Raging for two days, the storm scattered both fleets, severely damaging the French flagship.[59] Information technology besides frustrated plans past Sullivan to attack Newport without French support on xi Baronial.[60] While Sullivan awaited the return of the French fleet, he began siege operations, moving closer to the British lines on 15 August and opening trenches to the northeast of the fortified British line north of Newport the next 24-hour interval.[61]

As the 2 fleets sought to regroup, private ships encountered enemy ships, and at that place were several minor naval skirmishes; two French ships (including d'Estaing'southward flagship), already suffering storm damage, were badly mauled in these encounters.[59] The French fleet regrouped off Delaware, and returned to Newport on 20 August, while the British fleet regrouped at New York.[62]

Despite pressure from his captains to sail immediately for Boston to brand repairs, Admiral d'Estaing instead sailed for Newport to inform the Americans he would be unable to assist them. Upon his arrival on 20 Baronial he informed Sullivan, and rejected entreaties that the British could be compelled to surrender in just one or two days with their help. Of the conclusion, d'Estaing wrote: "It was [...] hard to persuade oneself that about half dozen thou men well entrenched and with a fort before which they had dug trenches could exist taken either in twenty-four hours or in 2 days".[63] Any idea of the French fleet remaining at Newport was likewise opposed by d'Estaing's captains, with whom he had a difficult relationship because of his arrival in the navy at a high rank after service in the French regular army.[63] D'Estaing sailed for Boston on 22 Baronial.[64]

D'Estaing attain Boston [edit]

A 1778 French armed forces map showing the positions of generals Lafayette and Sullivan around Newport Bay on xxx August 1778

The French determination brought on a moving ridge of anger in the American ranks and its commanders. Although General Greene penned a complaint that John Laurens termed "sensible and spirited", Full general Sullivan was less diplomatic.[64] In a cannonball containing much inflammatory language, he chosen d'Estaing'southward decision "derogatory to the laurels of French republic", and included further complaints in orders of the solar day that were later suppressed when cooler heads prevailed.[65] American writers from the ranks called the French decision a "desertion", and noted that they "left us in a virtually Rascally mode".[66]

The French difference prompted a mass exodus of the American militia, significantly shrinking the American force.[67] On 24 Baronial, Sullivan was alerted past General George Washington that Clinton was assembling a relief strength in New York. That evening his quango fabricated the determination to withdraw to positions on the northern role of the isle.[68] Sullivan connected to seek French assistance, dispatching Lafayette to Boston to negotiate further with d'Estaing.[69]

In the concurrently, the British in New York had non been idle. Lord Howe, concerned virtually the French fleet and farther reinforced by the inflow of ships from Byron's tempest-tossed squadron, sailed out to catch d'Estaing before he reached Boston. General Clinton organised a force of four,000 men nether Major Full general Charles Grey, and sailed with it on 26 August, destined for Newport.[70]

The inflammatory writings of General Sullivan arrived before the French fleet reached Boston; Admiral d'Estaing's initial reaction was reported to be a dignified silence. Under pressure level from Washington and the Continental Congress, politicians worked to smooth over the incident while d'Estaing was in skillful spirits when Lafayette arrived in Boston. D'Estaing even offered to march troops overland to back up the Americans: "I offered to get a colonel of infantry, under the control of i who three years ago was a lawyer, and who certainly must have been an uncomfortable man for his clients".[71]

General Pigot was harshly criticise by Clinton for failing to wait the relief force, which might accept successfully entrapped the Americans on the island.[72] He left Newport for England not long afterward. Newport was abandoned past the British in October 1779 with economic system ruined by the state of war.[73]

Other deportment [edit]

The relief strength of Clinton and Grey arrived at Newport on i September.[74] Given that the threat was over, Clinton instead ordered Grey to raid several communities on the Massachusetts coast.[75] Admiral Howe was unsuccessful in his bid to catch upwardly with d'Estaing, who held a strong position at the Nantasket Roads when Howe arrived there on thirty August.[76] Admiral Byron, who succeeded Howe as head of the New York station in September, was also unsuccessful in blockading d'Estaing: his armada was scattered past a tempest when it arrived off Boston, while d'Estaing sailed away, spring for the West Indies.[77] [78]

The British Navy in New York had not been inactive. Vice-Admiral Sir George Collier engaged in a number of amphibious raids against littoral communities from Chesapeake Bay to Connecticut, and probed at American defences in the Hudson River valley.[79] Coming upwards the river in force, he supported the cardinal outpost capture of Stony Point, only advanced no further. When Clinton weakened the garrison there to provide men for raiding expeditions, Washington organised a counterstrike. Brigadier Full general Anthony Wayne led a force that, solely using the bayonet, recaptured Stony Betoken.[eighty] The Americans chose not to concord the postal service, but their morale was dealt a blow later in the year, when their failure to co-operate with the French led to an unsuccessful attempt to dislodge the British from Savannah.[81] Control of Georgia was formally returned to its royal governor, James Wright, in July 1779, but the backcountry would non come up nether British control until after the 1780 Siege of Charleston.[82] Patriot forces recovered Augusta past siege in 1781, but Savannah remained in British hands until 1782.[83] The harm sustained at Savannah forced Marseillois, Zélé, Sagittaire, Protecteur and Experiment to render to Toulon for repairs.[84]

John Paul Jones in April 1778 led a raid on the western English town of Whitehaven, representing the first date past American forces outside of N America.

Yorktown Campaign [edit]

French and American planning for 1781 [edit]

Map of the eastern seaboard showing naval movements during the entrada

French war machine planners had to residue competing demands for the 1781 campaign. Later the unsuccessful American attempts of co-operation leading to failed assaults at Rhode Island and Savannah, they realised more than active participation in N America was needed.[85] However, they also needed to co-ordinate their actions with Spain, where there was potential interest in making an set on on the British stronghold of Jamaica. It turned out that the Spanish were not interested in operations against Jamaica until after they had dealt with an expected British try to reinforce besieged Gibraltar, and only wanted to exist informed of the movements of the W Indies armada.[86]

As the French fleet was preparing to depart Brest, France in March 1781, several important decisions were made. The W Indies armada, led by the Rear-Admiral Comte François Joseph Paul de Grasse, after operations in the Windward Islands, was directed to get to Cap-Français (present-day Cap-Haïtien, Haiti) to determine what resources would be required to help Castilian operations. Because of a lack of transports, French republic also promised six one thousand thousand livres to support the American state of war effort instead of providing additional troops.[87] The French fleet at Newport was given a new commander, the Comte Jacques-Melchior de Barras Saint-Laurent. He was ordered to have the Newport fleet to harass British shipping off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, and the French army at Newport was ordered to combine with Washington's army outside New York.[88] In orders that were deliberately not fully shared with General Washington, De Grasse was instructed to aid in North American operations later on his finish at Cap-Français. The French Lieutenant-General Comte Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau, was instructed to tell Washington that de Grasse might be able to assist, without making any commitment (Washington learned from John Laurens, stationed in Paris, that de Grasse had discretion to come north).[89] [ninety]

Opening moves [edit]

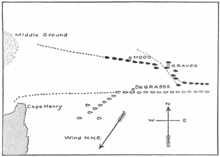

Tactical diagram of the Boxing of Greatcoat Henry:

A: fleets sight each other

B: outset tack

C: 2nd tack

D: disengagement

In Dec 1780, General Clinton sent Brigadier General Bridegroom Arnold (who had changed sides the previous September) with about one,700 troops to Virginia to carry out raiding and to fortify Portsmouth.[91] Washington responded by sending the Marquis de Lafayette south with a minor army to oppose Arnold.[92] Seeking to trap Arnold between Lafayette's army and a French naval detachment, Washington sought the Admiral Chevalier Destouches, the commander of the French fleet at Newport for help. Destouches was restrained by the larger British Due north American fleet anchored at Gardiner'southward Bay off the eastern finish of Long Island, and was unable to help.[93]

In early Feb, later on receiving reports of British ships damaged by a storm, Destouches decided to send a naval expedition from his base in Newport.[94] On 9 Feb, Captain Arnaud de Gardeur de Tilley sailed from Newport with three ships (transport of the line Eveille and frigates Surveillante and Gentile).[95] [96] When de Tilley arrived off Portsmouth four days later, Arnold retreated his ships, which had shallower drafts, up the Elizabeth River, where the larger French ships could not follow.[94] [97] Unable to assail Arnold's position, de Tilley could simply render to Newport.[98] On the way dorsum, the French captured HMS Romulus, a 44-gun frigate sent to investigate their movements.[97] This success and the pleas of General Washington, permitted Destouches to launch a total-scale operation. On 8 March, Washington was in Newport when Destouches sailed with his entire fleet, carrying one,200 troops for use in land operations when they arrived in the Chesapeake.[92] [93]

Vice-Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot, the British fleet commander in North America, was aware that Destouches was planning something, but did non learn of Destouches' sailing until x March, and immediately led his fleet out of Gardiner Bay in pursuit. He had the reward of favourable winds, and reached Cape Henry on 16 March, slightly ahead of Destouches.[93] Although suffering a tactical defeat, Arbuthnot was able to pull into Chesapeake Bay, thus frustrating the original intent of Destouches' mission, forcing the French fleet to render to Newport.[99] Later on transports delivered two,000 men to reinforce Arnold, Arbuthnot returned to New York. He resigned his mail as station chief in July and left for England, ending a stormy, difficult, and unproductive relationship with Full general Clinton.[100] [92]

Inflow of the fleets [edit]

The French fleet sailed from Brest on 22 March. The British fleet was busy with preparations to resupply Gibraltar, and did not attempt to oppose the departure.[101] Afterwards the French fleet sailed, the packet ship Concorde sailed for Newport, carrying the comte de Barras, Rochambeau's orders, and credits for the six million livres.[87] In a separate dispatch sent later, Admiral de Grasse also made two important requests. The first was that he be notified at Cap-Français of the state of affairs in North America so that he could make up one's mind how he might be able to assistance in operations there,[xc] and the second was that he exist supplied with 30 pilots familiar with Northward American waters.[101]

On 21 May Generals George Washington and the comte de Rochambeau, respectively the commanders of the American and French armies in Northward America, met to discuss potential operations against the British. They considered either an assail or siege on the principal British base of operations at New York City, or operations against the British forces in Virginia. Since either of these options would crave the help of the French fleet then in the West Indies, a transport was dispatched to meet with de Grasse who was expected at Cap-Français, outlining the possibilities and requesting his assistance.[102] Rochambeau, in a individual annotation to de Grasse, indicated that his preference was for an operation against Virginia. The two generals so moved their forces to White Plains, New York to study New York's defences and wait news from de Grasse.[103]

De Grasse arrived at Cap-Français on 15 August. He immediately dispatched his response, which was that he would make for the Chesapeake. Taking on three,200 troops, he sailed from Cap-Français with his unabridged fleet, 28 ships of the line. Sailing exterior the normal shipping lanes to avert notice, he arrived at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay on 30 August[103] and disembarked the troops to aid in the land blockade of Cornwallis.[104] Two British frigates that were supposed to be on patrol outside the bay were trapped inside the bay by de Grasse's arrival; this prevented the British in New York from learning the full strength of de Grasse'south armada until it was besides late.[105]

British Vice-Admiral Sir George Brydges Rodney had been warned that de Grasse was planning to take at least role of his fleet due north.[106] Although he had some clues that he might take his whole armada (he was aware of the number of pilots de Grasse had requested, for case), he assumed that de Grasse would not leave the French convoy at Cap-Français, and that part of his armada would escort it to French republic.[107] So Rodney accordingly divided his armada, sending Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood northward with fifteen ships of the line and orders to find de Grasse's destination in North America and report to New York.[108] Rodney, who was sick, took the rest of the fleet back to U.k. in society to recover, refit his fleet, and to avert the Atlantic hurricane flavor. Hood sailed from Antigua on 10 August, 5 days after de Grasse.[109] During the voyage, ane of his ships became separated and was captured past a privateer.[110]

Sailing more straight than de Grasse, Hood's fleet arrived off the entrance to the Chesapeake on 25 August.[3] Finding no French ships there, he and then sailed on to New York to meet with Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Graves, in command of the North American station post-obit Arbuthnot'south departure,[111] whom had spent several weeks trying to intercept a convoy organised past John Laurens to bring much-needed supplies and difficult currency from France to Boston.[112] When Hood arrived at New York, he found that Graves was in port (having failed to intercept the convoy), only had just five ships of the line that were fix for boxing.[three]

De Grasse had notified his analogue in Newport, the comte de Barras Saint-Laurent, of his intentions and his planned arrival date. De Barras sailed from Newport on 27 August with 8 ships of the line, 4 frigates, and 18 transports carrying French armaments and siege equipment. He deliberately sailed via a circuitous road to minimise the possibility of an encounter with the British, should they canvas from New York in pursuit. Washington and Rochambeau, in the meantime, had crossed the Hudson on 24 August, leaving some troops behind as a ruse to delay any potential motility on the part of Full general Clinton to mobilise assistance for Cornwallis.[three]

News of de Barras' departure led the British to realise that the Chesapeake was the probable target of the French fleets. By 31 August Graves had moved his ships over the bar at New York harbour. Taking command of the combined fleet, now 19 ships, Graves sailed south, and arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake on 5 September.[3] His progress was slow; the poor condition of some of the West Indies ships (opposite to claims by Admiral Hood that his fleet was fit for a month of service) necessitated repairs en route. Graves was besides concerned about some ships in his own armada; Europe in particular had difficulty manoeuvring.[113] The squadrons' clash started with Marseillois exchanging shots with the 64-gun HMS Intrepid, under Captain Anthony Molloy.[114]

Aftermath [edit]

The give up of Lord Cornwallis

The British retreat in disarray set up off a flurry of panic among the Loyalist population.[115] The news of the defeat was also non received well in London. King George 3 wrote (well before learning of Cornwallis'southward surrender) that "after the knowledge of the defeat of our armada [...] I nigh call back the empire ruined".[116]

The French success at completely encircling Cornwallis left them firmly in command of Chesapeake Bay.[117] In addition to capturing a number of smaller British vessels, de Grasse and de Barras assigned their smaller vessels to assist in the transport of Washington's and Rochambeau'south forces from Head of Elk, Maryland to Yorktown.[118]

It was not until 23 September that Graves and Clinton learned that the French fleet in the Chesapeake numbered 36 ships. This news came from a dispatch sneaked out by Cornwallis on the 17th, accompanied past a plea for help: "If you cannot relieve me very soon, you must be prepared to hear the worst".[119] After effecting repairs in New York, Admiral Graves sailed from New York on nineteen October with 25 ships of the line and transports carrying 7,000 troops to relieve Cornwallis.[120] It was 2 days later on Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown.[121] General Washington acknowledge to de Grasse the importance of his role in the victory: "You lot volition have observed that, whatever efforts are made past the country armies, the navy must take the casting vote in the present contest".[122] The eventual surrender of Cornwallis led to peace two years later and British recognition of the independent United States of America.[121]

Admiral de Grasse returned with his fleet to the Due west Indies. In a major date that suspended Franco-Spanish plans for the capture of Jamaica in 1782, he was defeated and taken prisoner by Rodney in the Battle of the Saintes.[123] His flagship Ville de Paris was lost at sea in a storm while being conducted dorsum to England equally office of a armada commanded by Admiral Graves. Despite the controversy over his carry in this battle, Graves continued to serve, rising to full admiral and receiving an Irish peerage.[124]

See also [edit]

- Quasi War

- War of 1812

Notes [edit]

- ^ Formal naval organisation did not begin until Washington took control in June 1775 (Callo 2006, pp. 22–23).

- ^ For example, Nelson 2008, p. 19, claims that no troops were stationed on Noddle's and Ketchum 1999, p. 69, implies as much. A Documentary History of Chelsea states (in testimony from British General Charles Sumner) that marines were present on the island.

- ^ This crossing was effected without Graves' guard boats taking notice (Nelson 2008, p. 18).

- ^ Sources disagree on which vessel; Polly and Unity are both mentioned; Volo 2008, p. 41, suggests that contempo scholarship favours Polly (Drisko 1904, p. fifty; Benedetto 2006, p. 94).

- ^ In warships, a breastwork refers to the armoured superstructure in the middle of the ship that did not extend all the way out to the sides of the ship

References [edit]

- ^ Sweetman 2002, p. eight.

- ^ Sweetman 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Mahan 1890, p. 389.

- ^ Sweetman 2002, pp. 11–12.

- ^ French 1911, pp. 219, 234–237.

- ^ McCullough 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Beatson 1804, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Nelson 2008, p. eighteen.

- ^ Brooks 1999, p. 108.

- ^ Beatson 1804, p. 73.

- ^ Morrissey 1995, p. 50.

- ^ Duncan 1992, p. 208.

- ^ Duncan 1992, p. 209.

- ^ Drisko 1904, p. 50.

- ^ Duncan 1992, p. 212.

- ^ a b Miller 1974, p. 49.

- ^ Duncan 1992, pp. 211–217.

- ^ Leamon 1995, pp. 67–72.

- ^ Caulkins & Griswold 1895, p. 516.

- ^ Charles 2008, pp. 168–169.

- ^ a b Miller 1997, p. 16.

- ^ Morison 1999, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Sweetman 2002, p. ane.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 17.

- ^ Field 1898, pp. 104.

- ^ Field 1898, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Field, pp. 100–102

- ^ Field 1898, pp. 108–113.

- ^ Morison 1999, pp. 67–68; Field 1898, p. 117

- ^ Field 1898, pp. 117–119.

- ^ a b Morgan 1959, p. 44.

- ^ Field 1898, p. 120.

- ^ a b Morison 1999, p. 70.

- ^ Field 1898, p. 120–121.

- ^ Field 1898, p. 125.

- ^ Thomas 2004, p. 52.

- ^ Morgan 1959, p. 47.

- ^ Morgan 1959, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Morgan 1959, p. 49.

- ^ Morgan 1959, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Ward 1952, p. 588.

- ^ Miller 1997, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. nineteen.

- ^ Howarth 1999, p. sixteen.

- ^ a b c Morrissey 1997, p. 77.

- ^ Schaeper 2011, pp. 152–153; Daughan 2011, p. 172

- ^ Douglas 1979.

- ^ Daughan 2011, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Morrissey 1997, p. 78.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 36, 49.

- ^ Mahan 1890, p. 361.

- ^ a b c Daughan 2011, p. 177.

- ^ a b Daughan 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 68–71.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 61.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 75.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 76.

- ^ a b Mahan 1890, p. 362.

- ^ Daughan 2011, p. 179.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Mahan 1890, p. 363.

- ^ a b Dearden 1980, p. 101.

- ^ a b Dearden 1980, p. 102.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 102, 135.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 106.

- ^ Daughan 2011, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 118.

- ^ Nelson 1985, p. 63.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 134.

- ^ Dearden 1980, p. 128.

- ^ Dearden 1980, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Nelson 1996, p. 63.

- ^ Nelson 1996, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Gruber 1972, p. 319.

- ^ Colomb 1895, p. 384.

- ^ Gruber 1972, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Ferling 2010, p. 196.

- ^ Leckie 1993, p. 502.

- ^ Leckie 1993, pp. 503–504.

- ^ Coleman 1991, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Coleman 1991, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Troude 1867, p. 46.

- ^ Dull 1975, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Dull 1975, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Dull 1975, p. 329.

- ^ Carrington 1876, p. 614.

- ^ Grainger 2005, p. xl.

- ^ a b Tedious 1975, p. 241.

- ^ Russell 2000, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b c Russell 2000, p. 254.

- ^ a b c Mahan 1898, p. 489.

- ^ a b Carrington 1876, p. 584.

- ^ Linder 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Campbell 1860, p. 717.

- ^ a b Linder 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Lockhart 2008, p. 245.

- ^ Perkins 1911, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Davis 1970, p. 45.

- ^ a b Dull 1975, p. 242.

- ^ Mahan 1890, p. 387.

- ^ a b Mahan 1890, p. 388.

- ^ Ketchum 2004, pp. 178–206.

- ^ Mahan 1890, p. 391.

- ^ Morrill 1993, p. 179.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 174.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 175.

- ^ Grainger 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 177.

- ^ Linder 2005, p. xiv.

- ^ Grainger 2005, p. 51.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 185.

- ^ Morrissey 1997, p. 55.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 225.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 272.

- ^ Ketchum 2004, p. 208.

- ^ Morrissey 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 227.

- ^ Grainger 2005, p. 135.

- ^ a b Grainger 2005, p. 185.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 270.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 277.

- ^ Larrabee 1964, p. 274.

Bibliography [edit]

- Beatson, Robert (1804). Naval and Military Memoirs of Groovy Britain, from 1727 to 1783. Vol. iv. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees & Orme. ISBN978-0-8398-0189-four. OCLC 669129181.

- Benedetto, William R. (2006). Sailing Into the Abyss: A True Story of Extreme Heroism on the High Seas. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN978-0-8065-2646-ane. OCLC 70683882.

- Brooks, Victor (1999). The Boston Campaign. Combined Publishing. ISBNone-58097-007-nine. OCLC 833471799.

- Callo, Joseph F (2006). John Paul Jones: America's First Sea Warrior. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN978-1-59114-102-0. OCLC 62281463.

- Campbell, Charles (1860). History of the Colony and Ancient Dominion of Virginia. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. OCLC 2109795.

- Carrington, Henry Beebe (1876). Battles of the American Revolution, 1775–1781. New York: A. S. Barnes. OCLC 33205321.

- Caulkins, Frances Manwaring; Griswold, Cecelia (1895). History of New London, Connecticut: From the First Survey of the Coast in 1612 to 1860. New London, Connecticut: H. D. Utley. OCLC 1856358.

- Chamberlain, Mellen, ed. (1908). A Documentary History of Chelsea: Including the Boston Precincts of Winnisimmet, Rumney Marsh, and Pullen Indicate 1624–1824. Vol. ii. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. OCLC 1172330.

- Charles, Patrick J (2008). Irreconcilable Grievances: The Events That Shaped American Independence. Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books. ISBN978-0-7884-4566-8. OCLC 212838026.

- Coleman, Kenneth (1991). A History of Georgia. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN978-0-8203-1269-nine. OCLC 21975722.

- Colomb, Philip (1895). Naval Warfare, its Ruling Principles and Practice Historically Treated. London: West. H. Allen. OCLC 2863262.

- Daughan, George (2011) [2008]. If By Sea: The Forging of the American Navy—from the Revolution to the War of 1812. Bones Books. ISBN978-0-465-02514-5. OCLC 701015376.

- Davis, Burke (1970). The Campaign That Won America: the Story of Yorktown . New York: Dial Press. OCLC 248958859.

- Dearden, Paul F. (1980). The Rhode Island Campaign of 1778. Providence, RI: Rhode Island Bicentennial Federation. ISBN978-0-917012-17-4. OCLC 60041024.

- Douglas, W. A. B. (1979). "BYRON, JOHN". Lexicon of Canadian Biography. Vol. iv. Academy of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 21 Nov 2016.

- Drisko, George Washington (1904). Narrative of the Boondocks of Machias, the Old and the New, the Early on and Late. Printing of the Republican. OCLC 6479739.

- Dull, Jonathan R (1975). The French Navy and American Independence: A Written report of Artillery and Affairs, 1774–1787. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-06920-3. OCLC 1500030.

- Duncan, Roger F. (1992). Coastal Maine: A Maritime History. New York: Norton. ISBN0-393-03048-two. OCLC 24142698.

- Ferling, John E (2010). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Printing. ISBN978-1-60819-095-9. OCLC 462908150.

- Field, Edward (1898). Esek Hopkins, Commander-in-Principal of the Continental Navy During the American Revolution, 1775 to 1778. Providence: Preston & Rounds. OCLC 3430958.

- French, Allen (1911). The Siege of Boston. Macmillan. OCLC 3927532.

- Grainger, John D. (2005). The Battle of Yorktown, 1781: A Reassessment. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN978-ane-84383-137-ii. OCLC 57311901.

- Gruber, Ira (1972). The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution. New York: Atheneum Press. ISBN978-0-8078-1229-vii. OCLC 1464455.

- Howarth, Stephen (1999). To Shining Sea: a History of the United States Navy, 1775–1998. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN0-8061-3026-1. OCLC 40200083.

- Ketchum, Richard One thousand (1999). Decisive Day: The Boxing for Bunker Loma. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN978-0-8050-6099-7. OCLC 40644809.

- Ketchum, Richard Thousand (2004). Victory at Yorktown: the Campaign That Won the Revolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN978-0-8050-7396-six. OCLC 54461977.

- Larrabee, Harold A (1964). Conclusion at the Chesapeake . New York: Clarkson N. Potter. OCLC 426234.

- Leamon, James Due south (1995). Revolution Downeast: The War for American Independence in Maine. Amherst: Academy of Massachusetts Press. ISBN978-0-87023-959-v.

- Leckie, Robert (1993). George Washington's War: The Saga of the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-06-092215-3. OCLC 29748139.

- Linder, Bruce (2005). Tidewater's Navy: an Illustrated History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Printing. ISBN978-one-59114-465-6. OCLC 60931416.

- Lockhart, Paul (2008). The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army. New York: Smithsonian Books (HarperCollins). ISBN978-0-06-145163-8. OCLC 191930840.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1890). the Influence of sea power upon history, 1660–1783. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 8673260.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1898). Major Operations of the Imperial Navy, 1762–1783. Boston: Piddling, Dark-brown and Company. OCLC 3012050.

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN0-7432-2672-0. OCLC 57557578.

- Miller, Nathan (1974). Sea of Glory: The Continental Navy Fights for Independence, 1775–1783 . New York: David McKay Company. ISBN978-0-679-50392-seven. OCLC 844299. Retrieved xvi December 2016.

- Miller, Nathan (1997). The U.S. Navy: A History (third ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN1-55750-595-0. OCLC 37211290.

- Morgan, William James (1959). Captains to the Northward. Barre, MA: Barre Publishing. OCLC 1558276.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1999) [1959]. John Paul Jones: A Sailor'due south Biography. Annapolis: Naval Institute Printing. ISBN978-1-55750-410-4. OCLC 42716061.

- Morrill, Dan (1993). Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution . Baltimore: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America. ISBN1-877853-21-6. OCLC 29357639.

- Morrissey, Brendan (1995). Boston 1775: The Shot Heard Around the Earth. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-one-85532-362-9. OCLC 33042763.

- Morrissey, Brendan (1997). Yorktown 1781: the Globe Turned Upside Down. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-one-85532-688-0. OCLC 39028166.

- Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne, Soldier of the Early Commonwealth. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN978-0-253-30751-4. OCLC 11518827.

- Nelson, James L. (2008). George Washington'south Clandestine Navy: How the American Revolution Went to Sea . New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN978-0-07-149389-v. OCLC 212627064.

- Nelson, Paul David (1996). Sir Charles Grey, Showtime Earl Grey: Royal Soldier, Family Patriarch. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN978-0-8386-3673-2. OCLC 33820307.

- Perkins, James Breck (1911). France in the American Revolution. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 177577.

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-0783-five. OCLC 44562323.

- Schaeper, Thomas (2011). Edward Bancroft: Scientist, Writer, Spy . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-11842-1. OCLC 178289618.

- Sweetman, Jack (2002). American Naval History: An Illustrated Chronology of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, 1775–present . Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN1-55750-867-4. OCLC 48046120.

- Thomas, Evan (2004). John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Begetter of the American Navy. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-0-7432-5804-3. OCLC 56321227.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France (in French). Vol. two. Challamel ainé. OCLC 18683121.

- Volo, James Thousand (2008). Blue Water Patriots: The American Revolution Adrift. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-0-7425-6120-5. OCLC 209652239.

- Ward, Christopher (1952). War of the Revolution . New York: Macmillan. OCLC 214962727.

Farther reading [edit]

- Clark, William Bell, ed. (1964). Naval Documents Of The American Revolution, Volume 1 (December. 1774 - Sept. 1775). Washington D.C., U.S. Navy Department.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_battles_of_the_American_Revolutionary_War

0 Response to "what did the british navy try to stop the americans from doing"

Post a Comment